Decline and fall: how American society unravelled

Thirty years ago, the old deal that held US society together started to unwind, with social cohesion sacrificed to greed. Was it an inevitable process – or was it engineered by self-interested elites?

Youngstown, Ohio, was once a thriving steel centre. Now, the industry has all gone and the city is full of abandoned homes and businesses. Photograph: Brian Snyder/Reuters

In or around 1978, America's character changed. For almost half a century, the United States had been a relatively egalitarian, secure, middle-class democracy, with structures in place that supported the aspirations of ordinary people. You might call it the period of the Roosevelt Republic. Wars, strikes, racial tensions and youth rebellion all roiled national life, but a basic deal among Americans still held, in belief if not always in fact: work hard, follow the rules, educate your children, and you will be rewarded, not just with a decent life and the prospect of a better one for your kids, but with recognition from society, a place at the table.

This unwritten contract came with a series of riders and clauses that left large numbers of Americans – black people and other minorities, women, gay people – out, or only halfway in. But the country had the tools to correct its own flaws, and it used them: healthy democratic institutions such as Congress, courts, churches, schools, news organisations, business-labour partnerships. The civil rights movement of the 1960s was a nonviolent mass uprising led by black southerners, but it drew essential support from all of these institutions, which recognised the moral and legal justice of its claims, or, at the very least, the need for social peace. The Roosevelt Republic had plenty of injustice, but it also had the power of self-correction.

Americans were no less greedy, ignorant, selfish and violent then than they are today, and no more generous, fair-minded and idealistic. But the institutions of American democracy, stronger than the excesses of individuals, were usually able to contain and channel them to more useful ends. Human nature does not change, but social structures can, and they did.

At the time, the late 1970s felt like shapeless, dreary, forgettable years.Jimmy Carter was in the White House, preaching austerity and public-spiritedness, and hardly anyone was listening. The hideous term "stagflation", which combined the normally opposed economic phenomena of stagnation and inflation, perfectly captured the doldrums of that moment. It is only with the hindsight of a full generation that we can see how many things were beginning to shift across the American landscape, sending the country spinning into a new era.

In Youngstown, Ohio, the steel mills that had been the city's foundation for a century closed, one after another, with breathtaking speed, taking 50,000 jobs from a small industrial river valley, leaving nothing to replace them. In Cupertino, California, the Apple Computer Company released the first popular personal computer, the Apple II. Across California, voters passed Proposition 13, launching a tax revolt that began the erosion of public funding for what had been the country's best school system. In Washington, corporations organised themselves into a powerful lobby that spent millions of dollars to defeat the kind of labour and consumer bills they had once accepted as part of the social contract. Newt Gingrich came to Congress as a conservative Republican with the singular ambition to tear it down and build his own and his party's power on the rubble. On Wall Street, Salomon Brothers pioneered a new financial product called mortgage-backed securities, and then became the first investment bank to go public.

A steelworker in Youngstown, Ohio, in 1947. Under the old deal, his hard work was to be rewarded. Photograph: Willard R. Culver/National Geographic/Corbis

A steelworker in Youngstown, Ohio, in 1947. Under the old deal, his hard work was to be rewarded. Photograph: Willard R. Culver/National Geographic/Corbis

The large currents of the past generation – deindustrialisation, the flattening of average wages, the financialisation of the economy, income inequality, the growth of information technology, the flood of money into Washington, the rise of the political right – all had their origins in the late 70s. The US became more entrepreneurial and less bureaucratic, more individualistic and less communitarian, more free and less equal, more tolerant and less fair. Banking and technology, concentrated on the coasts, turned into engines of wealth, replacing the world of stuff with the world of bits, but without creating broad prosperity, while the heartland hollowed out. The institutions that had been the foundation of middle-class democracy, from public schools and secure jobs to flourishing newspapers and functioning legislatures, were set on the course of a long decline. It as a period that I call the Unwinding.

In one view, the Unwinding is just a return to the normal state of American life. By this deterministic analysis, the US has always been a wide-open, free-wheeling country, with a high tolerance for big winners and big losers as the price of equal opportunity in a dynamic society. If the US brand of capitalism has rougher edges than that of other democracies, it is worth the trade-off for growth and mobility. There is nothing unusual about the six surviving heirs to the Walmart fortunepossessing between them the same wealth as the bottom 42% of Americans – that's the country's default setting. Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates are the reincarnation of Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie, Steven Cohen is another JP Morgan, Jay-Z is Jay Gatsby.

The rules and regulations of the Roosevelt Republic were aberrations brought on by accidents of history – depression, world war, the cold war – that induced Americans to surrender a degree of freedom in exchange for security. There would have been no Glass-Steagall Act, separating commercial from investment banking, without the bank failures of 1933; no great middle-class boom if the US economy had not been the only one left standing after the second world war; no bargain between business, labour and government without a shared sense of national interest in the face of foreign enemies; no social solidarity without the door to immigrants remaining closed through the middle of the century.

Once American pre-eminence was challenged by international competitors, and the economy hit rough seas in the 70s, and the sense of existential threat from abroad subsided, the deal was off.Globalisation, technology and immigration hurried the Unwinding along, as inexorable as winds and tides. It is sentimental at best, if not ahistorical, to imagine that the social contract could ever have survived – like wanting to hang on to a world of nuclear families and manual typewriters.

This deterministic view is undeniable but incomplete. What it leaves out of the picture is human choice. A fuller explanation of the Unwinding takes into account these large historical influences, but also the way they were exploited by US elites – the leaders of the institutions that have fallen into disrepair. America's postwar responsibilities demanded co-operation between the two parties in Congress, and when the cold war waned, the co-operation was bound to diminish with it. But there was nothing historically determined about the poisonous atmosphere and demonising language that Gingrich and other conservative ideologues spread through US politics. These tactics served their narrow, short-term interests, and when the Gingrich revolution brought Republicans to power in Congress, the tactics were affirmed. Gingrich is now a has-been, but Washington today is as much his city as anyone's.

It was impossible for Youngstown's steel companies to withstand global competition and local disinvestment, but there was nothing inevitable about the aftermath – an unmanaged free-for-all in which unemployed workers were left to fend for themselves, while corporate raiders bought the idle hulks of the mills with debt in the form of junk bonds and stripped out the remaining value. It may have been inevitable that the constraints imposed on US banks by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 would start to slip off in the era of global finance. But it was a political choice on the part of Congress and President Bill Clinton to deregulate Wall Street so thoroughly that nothing stood between the big banks and the destruction of the economy.

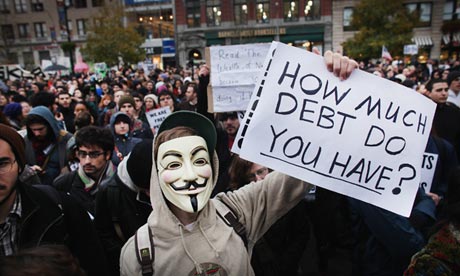

One of the 99%: an Occupy Wall Street protester in Union Square, New York, in 2011. Photograph: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

One of the 99%: an Occupy Wall Street protester in Union Square, New York, in 2011. Photograph: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Much has been written about the effects of globalisation during the past generation. Much less has been said about the change in social norms that accompanied it. American elites took the vast transformation of the economy as a signal to rewrite the rules that used to govern their behaviour: a senator only resorting to the filibuster on rare occasions; a CEO limiting his salary to only 40 times what his average employees made instead of 800 times; a giant corporation paying its share of taxesinstead of inventing creative ways to pay next to zero. There will always be isolated lawbreakers in high places; what destroys morale below is the systematic corner-cutting, the rule-bending, the self-dealing.

Earlier this year, Al Gore made $100m (£64m) in a single month by selling Current TV to al-Jazeera for $70m and cashing in his shares of Apple stock for $30m. Never mind that al-Jazeera is owned by the government of Qatar, whose oil exports and views of women and minorities make a mockery of the ideas that Gore propounds in a book or film every other year. Never mind that his Apple stock came with his position on the company's board, a gift to a former presidential contender. Gore used to be a patrician politician whose career seemed inspired by the ideal of public service. Today – not unlike Tony Blair – he has traded on a life in politics to join the rarefied class of the global super-rich.

It is no wonder that more and more Americans believe the game is rigged. It is no wonder that they buy houses they cannot afford and then walk away from the mortgage when they can no longer pay. Once the social contract is shredded, once the deal is off, only suckers still play by the rules.

George Packer's The Unwinding is published by Faber & Faber at £20